June 17th 2021 until May 22th 2022

Trailer

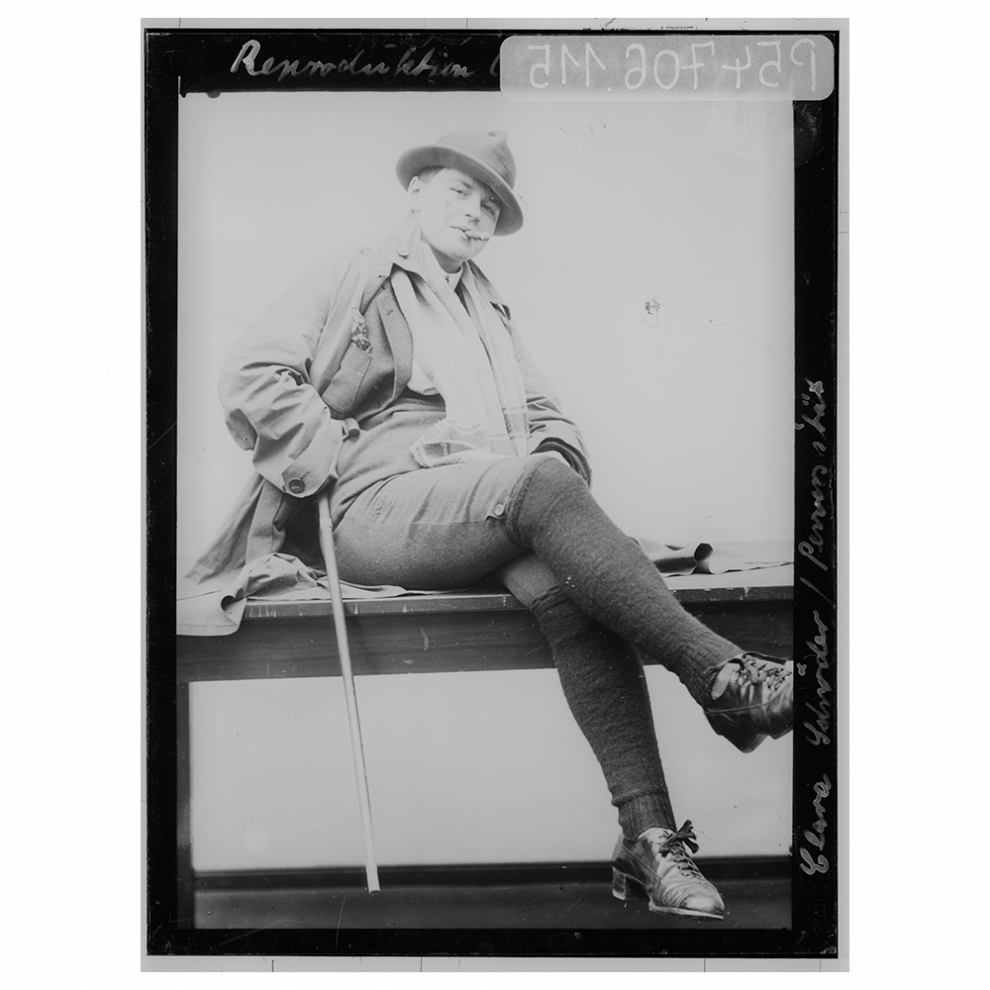

Homosexuals and lesbians in the 1920

The hope of emancipation

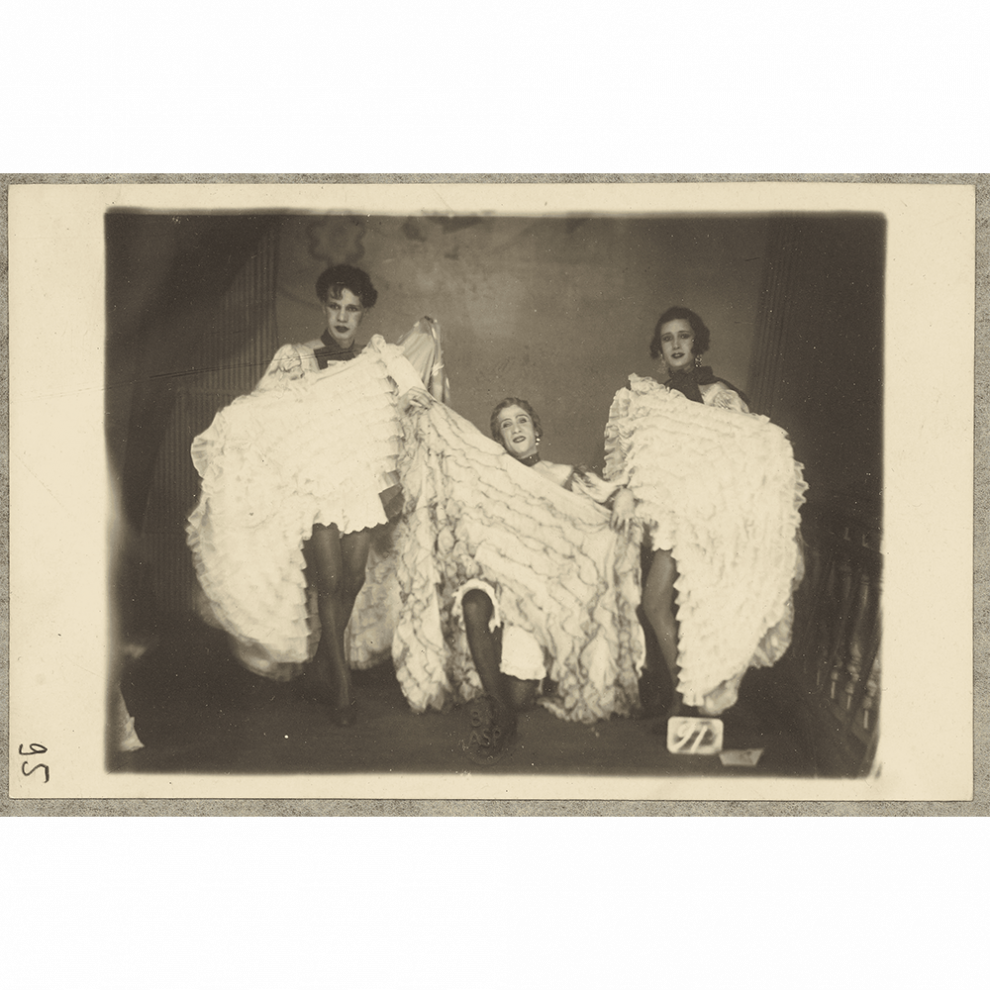

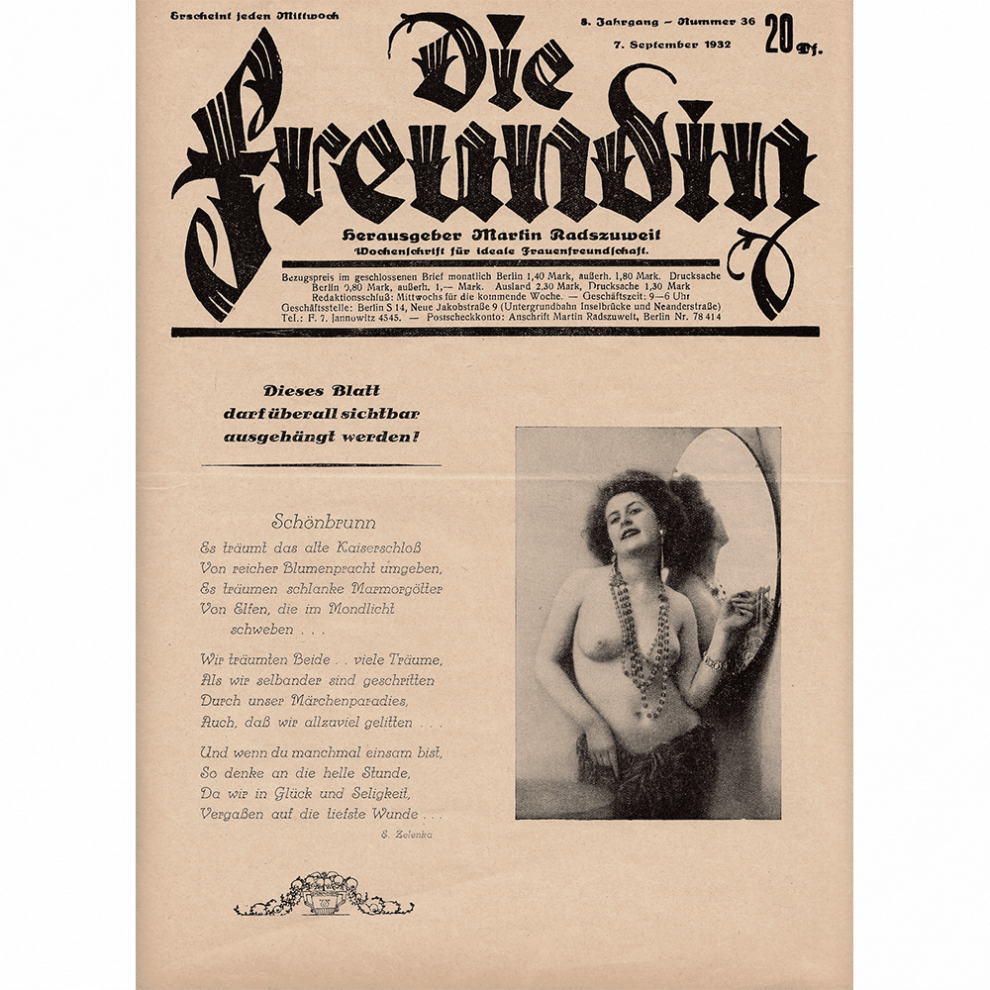

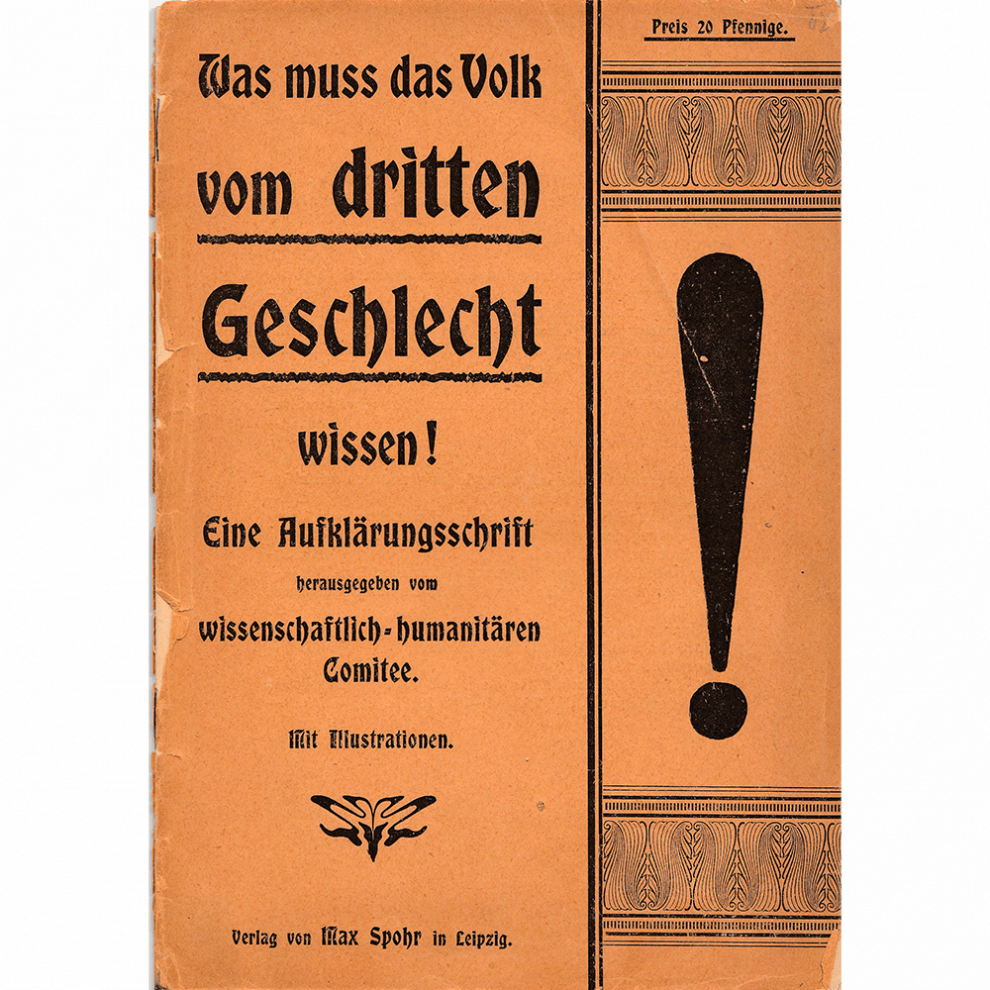

The earliest homosexual movements emerged in late 19th century Germany. In 1897, Magnus Hirschfeld founded the Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee (ScientificHumanitarian Committee), which campaigned for the repeal of Paragraph 175, published several newspapers, including Die Freundschaft and Die Freundin, organized conferences, held lectures and circulated petitions, with little success. In France, the magazine Inversions (1924) was quickly censored. During the Roaring Twenties, homosexuals and lesbians gathered at bars, cabarets (the Eldorado in Berlin and Le Monocle in Paris), private salons such as the one hosted by American poet Natalie Barney in Paris and large transvestite balls like Magic-City, also in Paris. Homosexuality also found a place in art (Christian Schad, Jeanne Mammen, etc.), literature (André Gide’s Corydon, 1924, Klaus Mann’s The Pious Dance, 1926, Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness, 1928, Colette’s These Pleasures, 1932, Christopher Isherwood’s Goodbye to Berlin, 1939, etc.) and film (Richard Oswald’s Anders als die Andern, 1919, Leontine Sagan’s Mädchen in Uniform, 1931).

But for most people, discretion remained the rule. Some contracted fake marriages and led double lives. Codes (slang, colors like purple or mauve) were used to identify each other in an overwhelmingly hostile society.

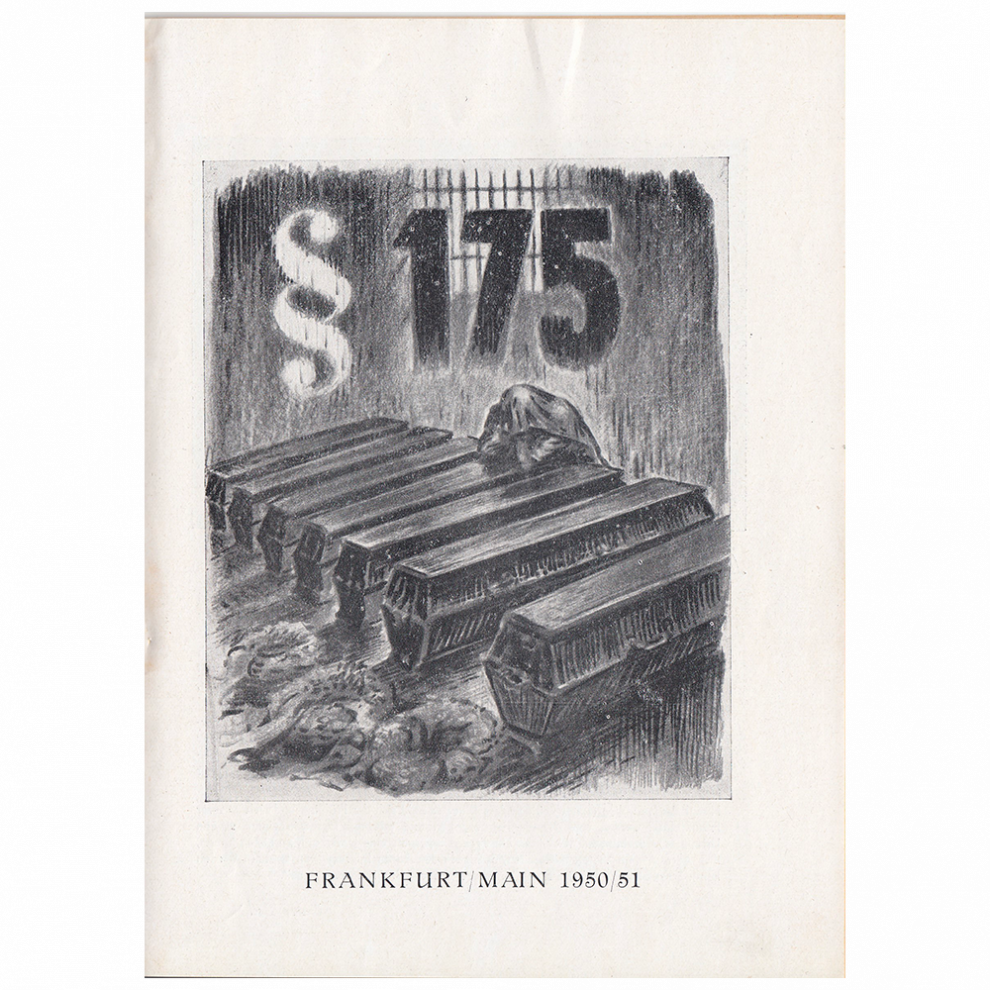

What is paragraph (§) 175?

Paragraph 175 of the German Penal Code remained in force from 1871 to 1994. From 1871 to 1935, only “unnatural lewdness”, understood by jurisprudence as “acts resembling coitus”, whether between men or between men and animals, was criminalized. From 1935, “lewdness” in general fell within the scope of the law, broadening its application. Paragraph 175a then criminalized “aggravated” sexual acts between men (“seduction” by an adult of a minor under 21, prostitution, use of force or authority), punishable by up to 10 years of hard labor. The FRG kept the 1935 version until 1969, while the GDR reverted to the 1871 version until 1968. Discrimination based on the age of sexual majority remained in force until 1994.

The Nazi period alone accounted for nearly 40% of convictions, and sentences were harsher on average. However, it should be recalled that the great majority of homosexuals managed to survive this period, even though the regime constantly targeted them.

The weight of homophobia

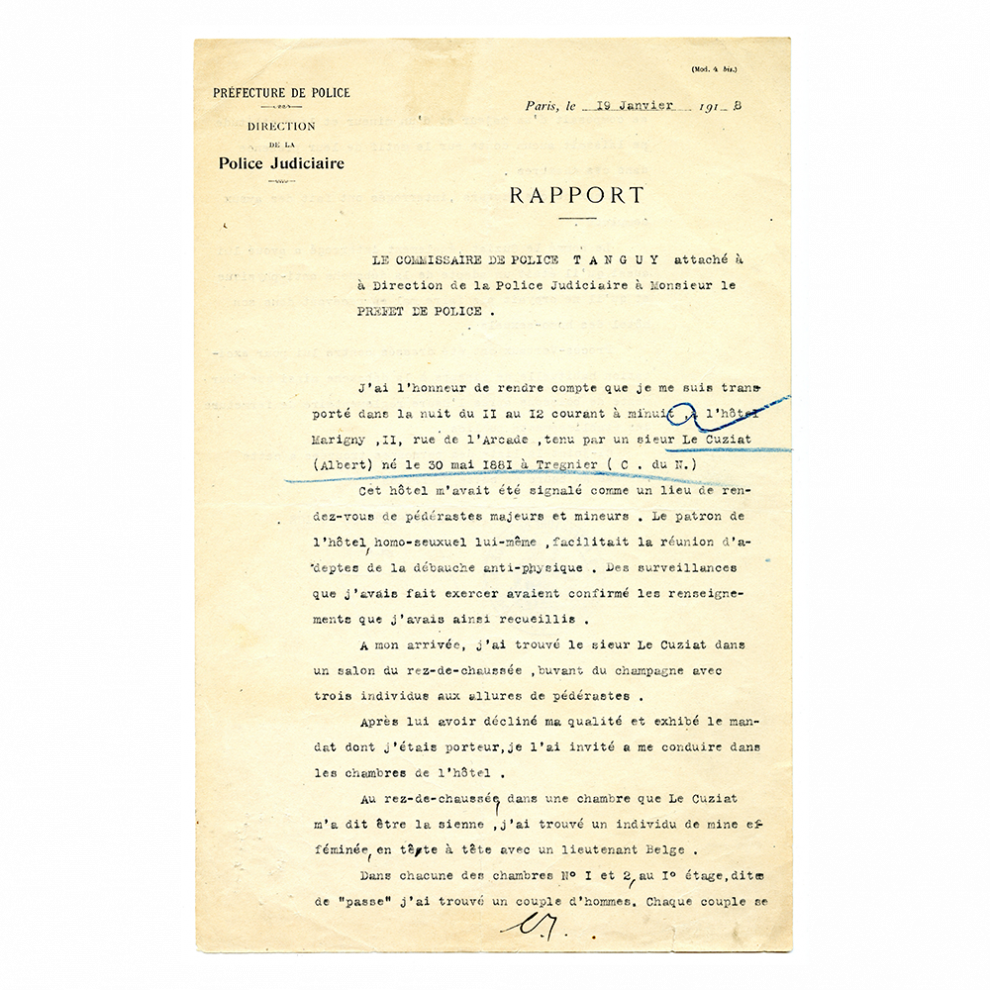

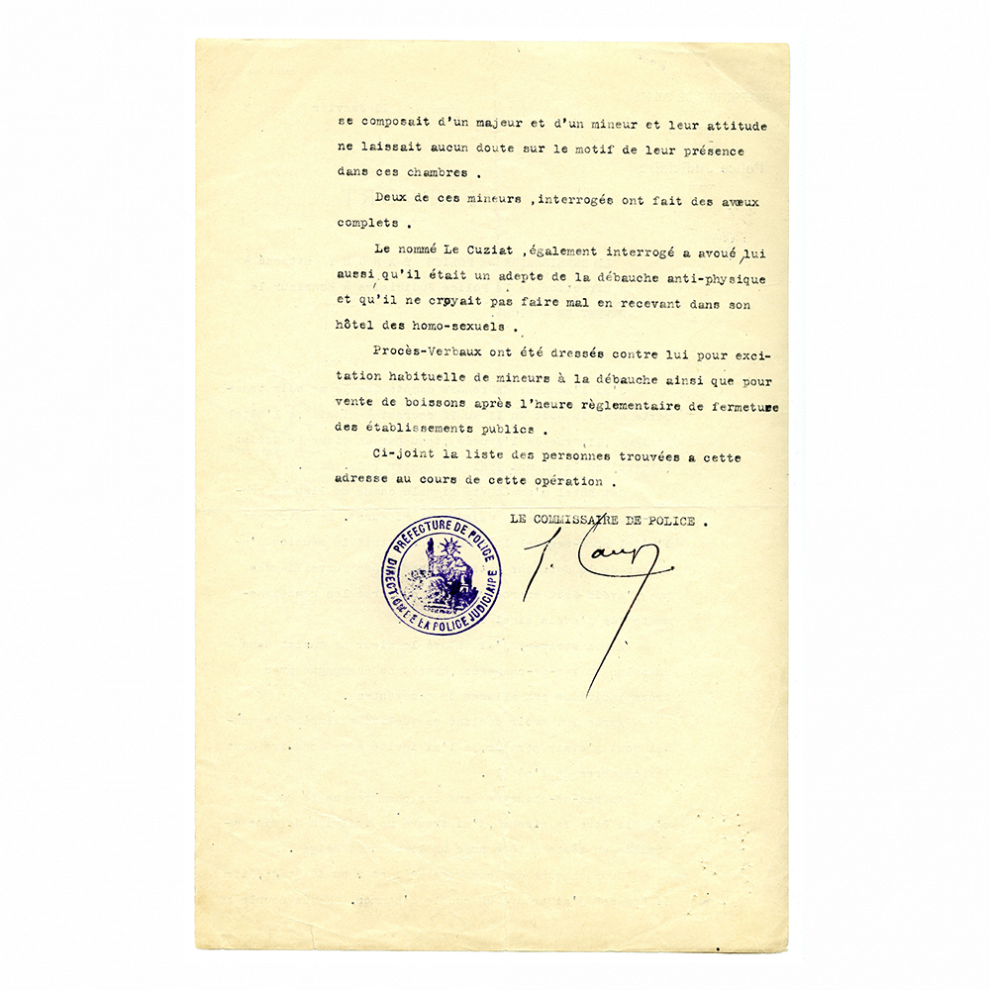

In 1791, France gained a lasting reputation for tolerance by abolishing the crime of sodomy, which had been punishable by death. Influenced by the napoleonic code, some countries, such as Italy and Belgium, followed suit, but others, including Germany and Great Britain, continued to punish sexual relations between men with imprisonment. Because lesbians were made invisible, only a few places, including Austria, Sweden and some Swiss cantons, criminalized relations between women. But even in countries where homosexuality was legal, the police kept a watchful eye on cruising places such as urinals, public gardens and bars, and it was possible to be prosecuted for public indecency or in cases involving minors.

Moreover, while many deemed homosexuality a sin, numerous doctors considered it a form of depravity or a perversion that in some cases could be “cured”. Stereotypes were common: “inverts” were effeminate, lesbians masculine. Homosexuals, a “free-masonry of vice”, were viewed as potential traitors, especially since homosexuality was portrayed as a foreign import (the “German vice” in France). Lesbians were said to infiltrate feminist movements. All were blamed for “corrupting youth”.

Portraits

Magnus Hirschfeld (1868-1935)

On May 14, 1897 in Berlin, sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld founded the Wissenchaftlich-humanitäres Komitee (WhK, Humanitarian Scientific Committee), the world’s first homosexual rights organization.

Homosexuality and nazism: discourse, forms and stages of repression

Ambiguous and contradictory messages

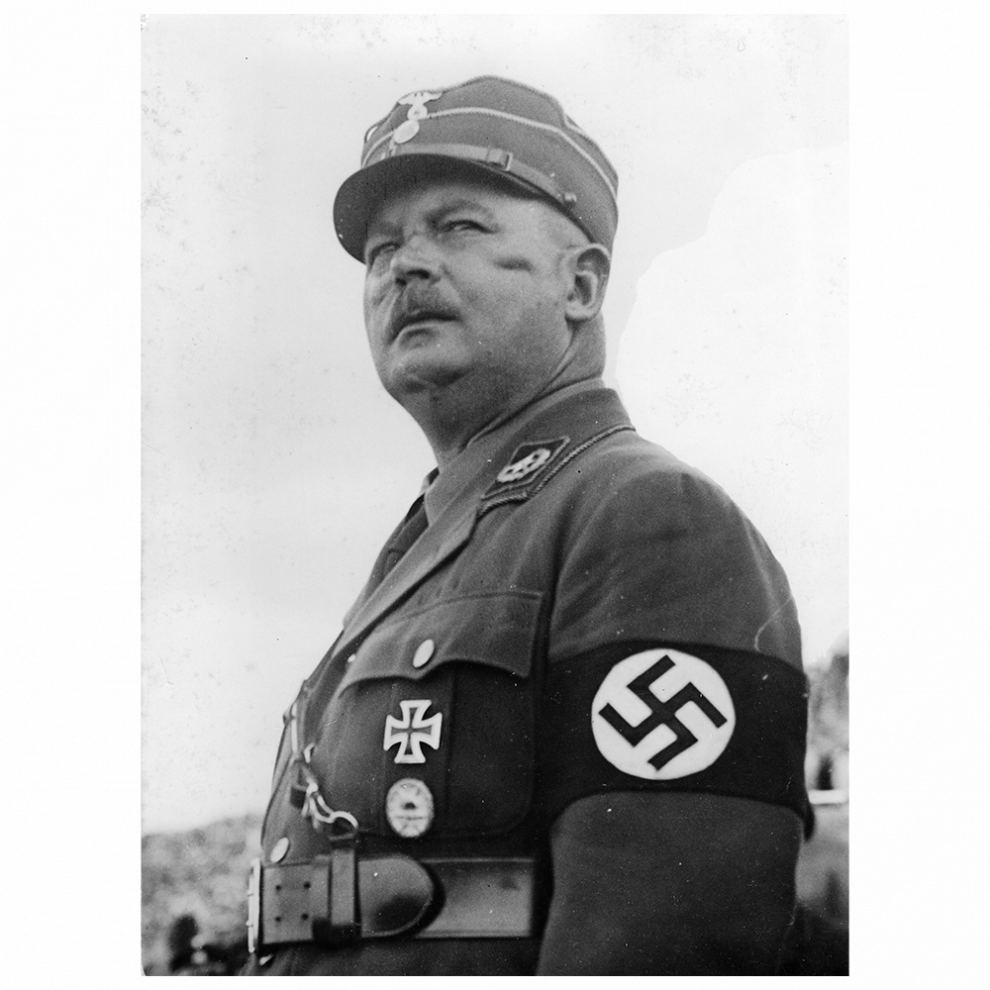

The position of the NSDAP, the Nazi Party, on homosexuality long remained ambiguous. Nazi organizations such as the SA, SS and Hitler Youth glorified friendship between men on the basis of Männerbund—the idea that male bonding is the cornerstone of society. It was well known that SA chief Ernst Röhm was homosexual. The Nazi regime also used homoerotic aesthetics, conspicuous, for example, in Arno Breker and Joseph Thorak’s monumental sculptures or Leni Riefenstahl’s films. From 1934, communist propaganda called homosexuality a “fascist perversion”, a cliché taken up by German exiles that persisted until well after the war (Luchino Visconti’s The Damned, 1969).

Some Nazi leaders, starting with Heinrich Himmler, used radical homophobic rhetoric very early on, condemning homosexuality as one result of race mixing. In 1927 and 1928, the NSDAP opposed the repeal of Paragraph 175. Nazis assaulted Magnus Hirschfeld on several occasions at his rallies in Munich. To them, homosexuals had no social worth. In a context of demographic anxiety and the need to conquer Lebensraum, if homosexuals refused to bend to the will of the German nation (getting married and having children), they had to be brought into line, “cured” and “reeducated”, if not eliminated.

Staged implementation

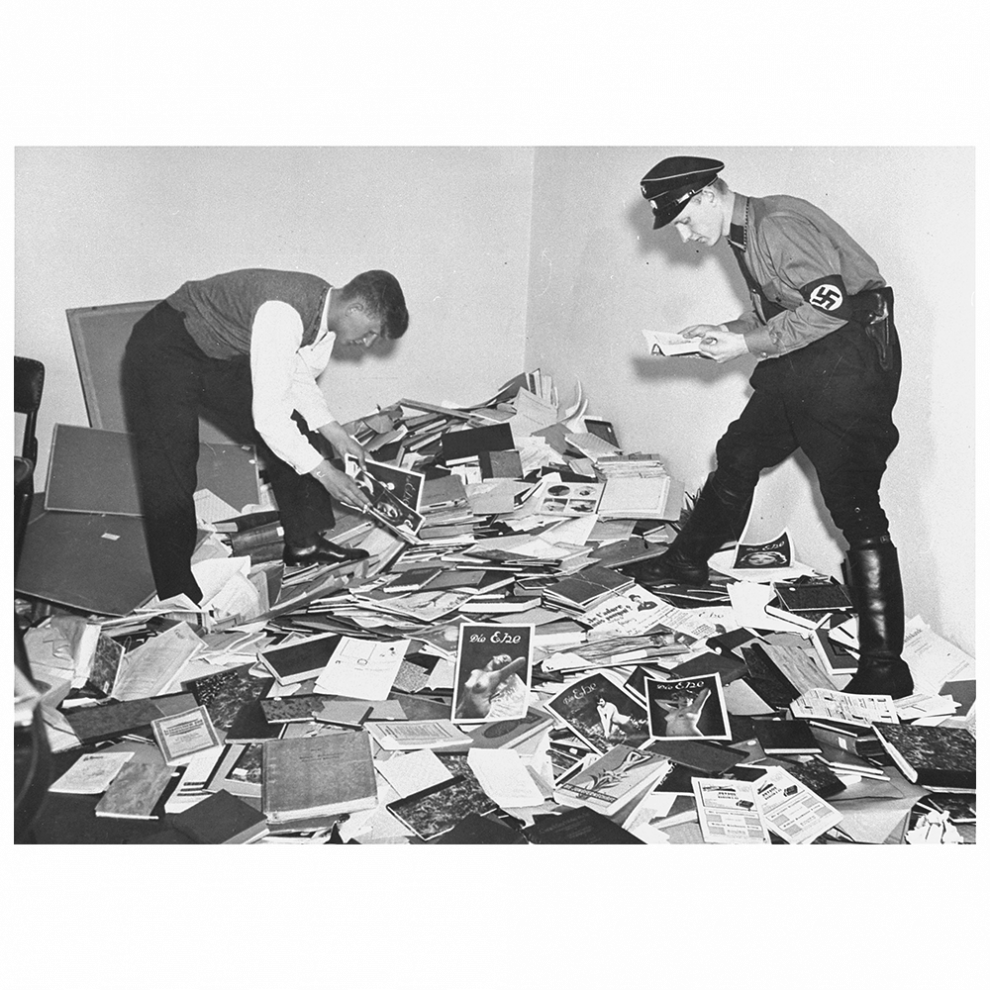

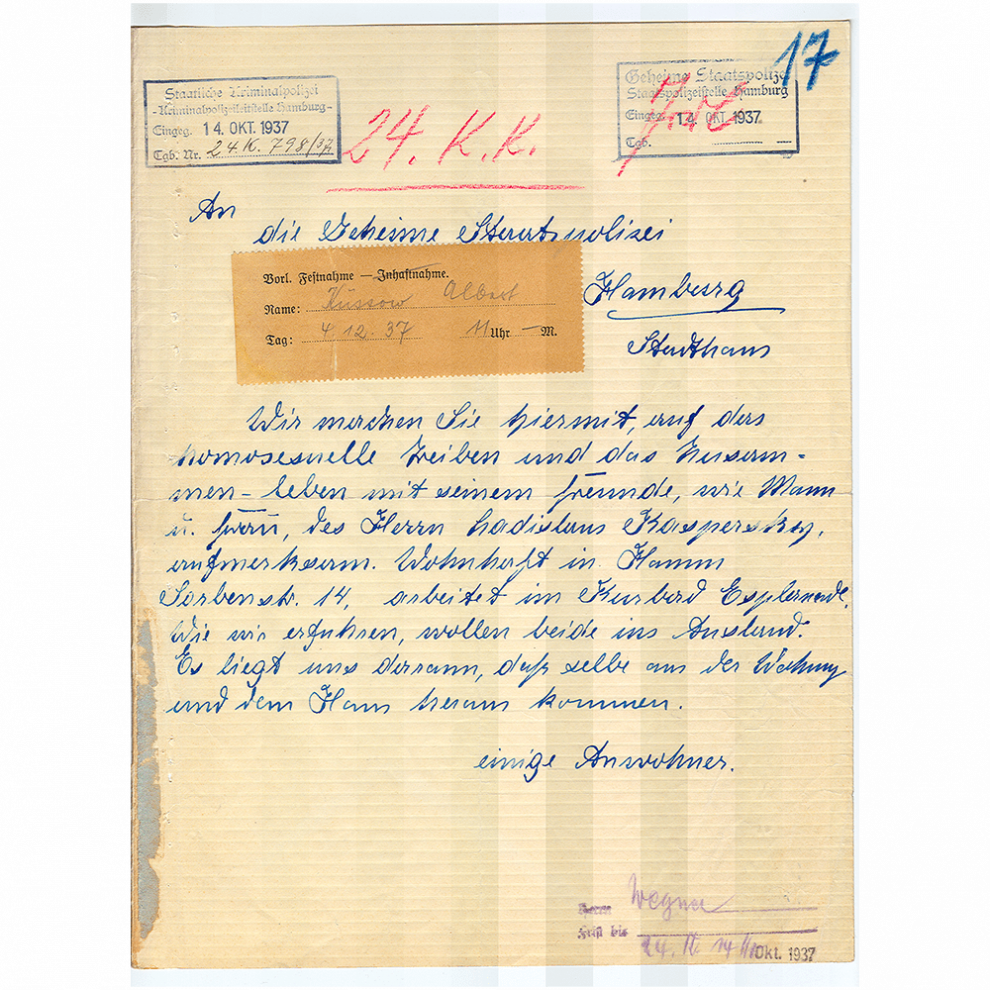

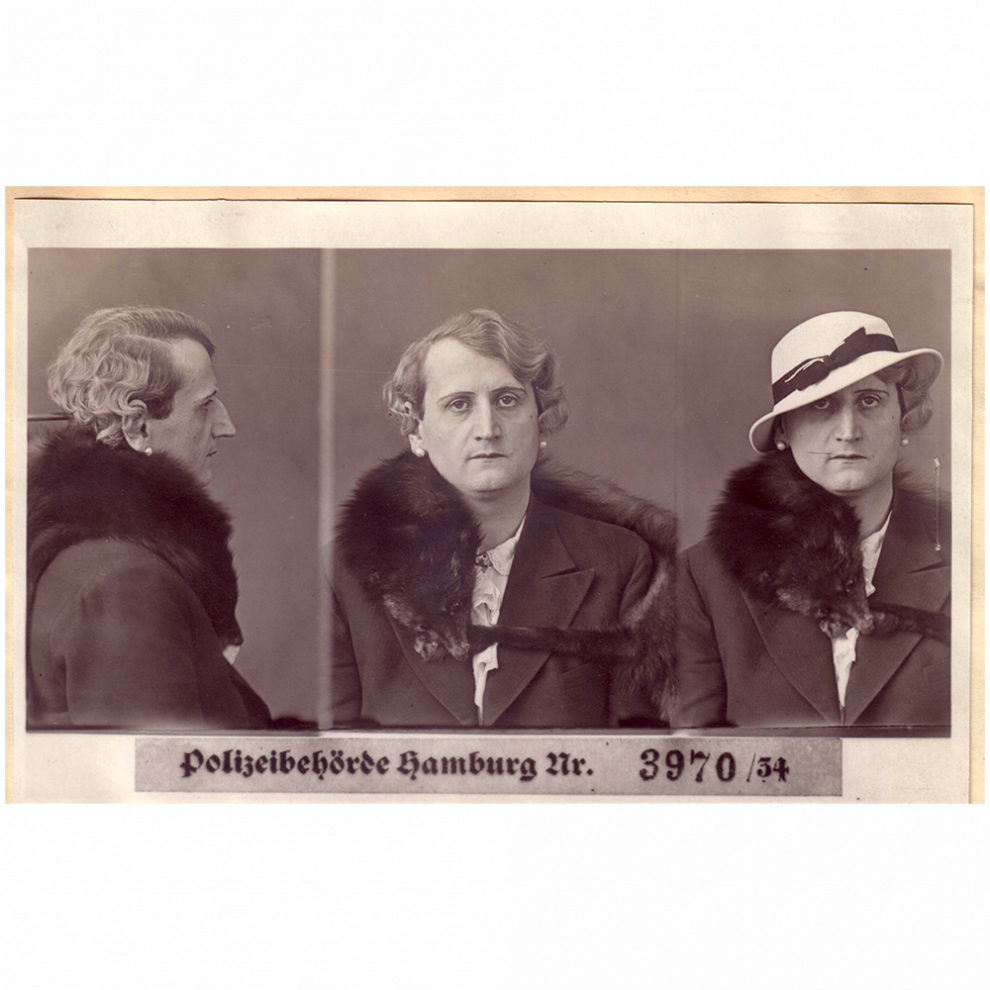

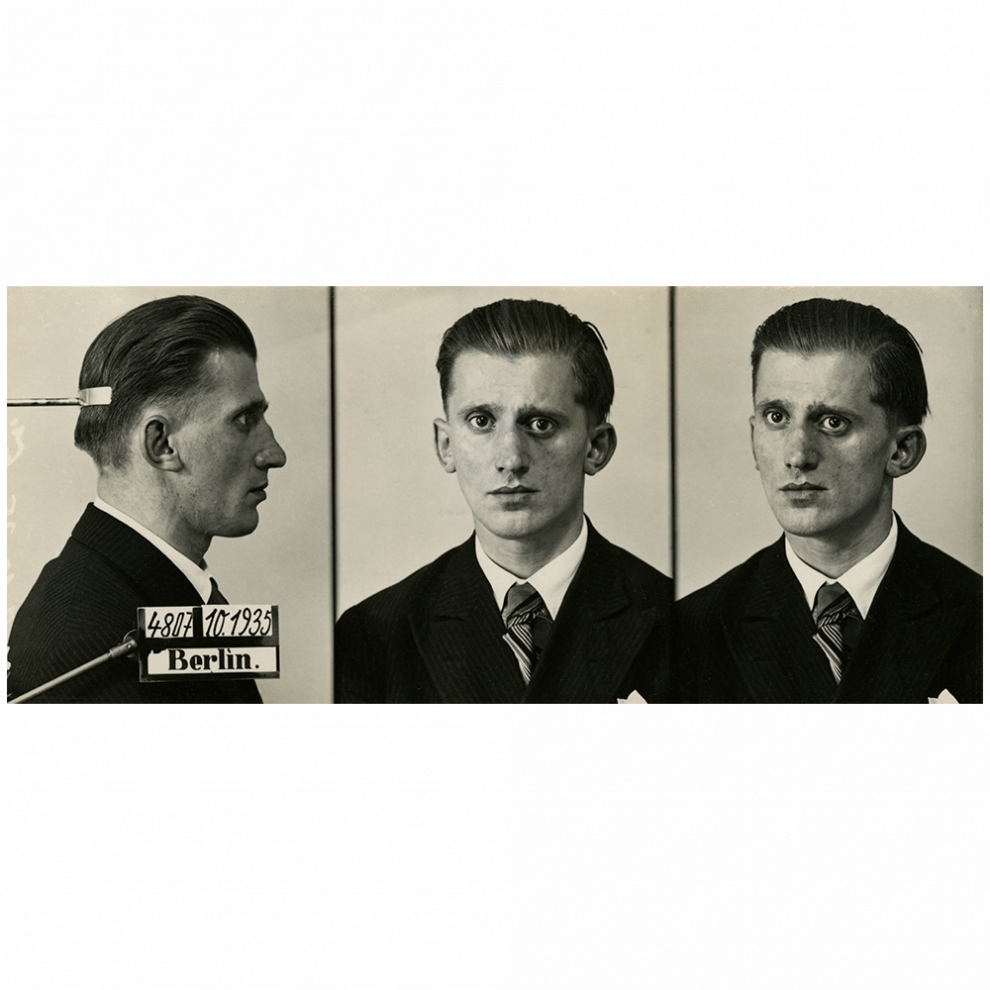

Almost as soon as Hitler became chancellor, in February 1933, homosexual magazines were banned, clubs closed and activist organizations dissolved. At first, Berlin bore the brunt of the crackdown; it was implemented unevenly, and sometimes later, in the rest of Germany. After a decree on February 10, 1934, prostitutes, transvestites, “corrupters of youth” and “repeat offenders” were the first to be arrested. In the beginning, they were incarcerated at Columbia-Haus in Berlin-Tempelhof. Then some were sent to Lichtenburg, Dachau and other concentration camps, sometimes without trial.

Röhm’s murder on “The Night of the Long Knives” (June 29-30, 1934) was a turning point. On September 1, 1935, Paragraph 175 was amended. Any sexual act or sign of desire between men was outlawed. The most serious cases were punishable by 10 years of hard labor.

Portraits

Robert Oelbermann (1896-1941)

and Rudi Pallas (1907-1952)

As part of a campaign against the former youth movements, Robert Oelbermann, founder of the Nerother Bund, was sentenced in September 1936 to twenty-one months of hard labour under §175. After eighteen months, he was sent to Sachsenhausen, where he organized, with Rudi Pallas, former Scout leader and other pink triangle, resistance activities with homosexual and political deportees.

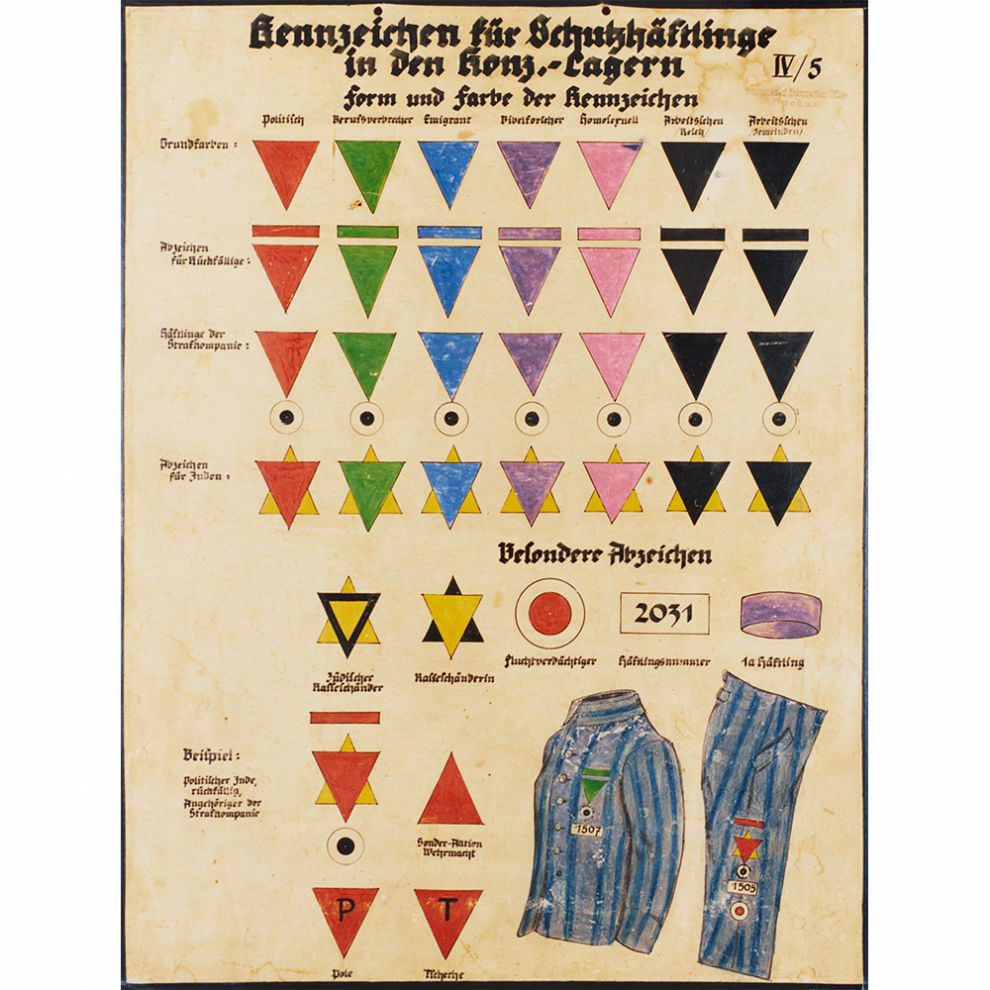

The pink triangles and the deportation of homosexuals

The plight of the pink triangles in the camps

Men convicted under Paragraph 175 met with varying fates. Most were imprisoned, but a minority was sent to concentration camps before or after serving their sentences in order to be “reeducated” by work. Some, considered “cured”, were then drafted into the Wehrmacht. Others were interned in mental hospitals and sometimes “euthanized”. Those convicted by military tribunals were executed or sent on suicide missions. A rare few were released. However, “exterminating” all homosexuals was never under consideration.

The pink triangles endured inhumane conditions in the camps. They were often assigned to the disciplinary company and the hardest tasks, such as working in the clay quarry at Sachsenhausen. Some were castrated, others subjected to medical experiments. Isolation made matters worse. The pink triangles never accounted for more than 1% of the camps’ total population. They were frequently isolated in separate barracks for fear of “contaminating” the other detainees, who were often hostile to them and lumped them together with the kapos who extorted sexual favors from prisoners. At certain times, they were at the bottom of the camps’ hierarchy, just one notch above the Jews.

Portrait

Josef Kohout (1919-1994)

The Austrian Josef Kohout was sentenced in September 1939 to seven months imprisonment for homosexuality, but was then sent to Sachsenhausen and then to Flossenbürg in May 1940.

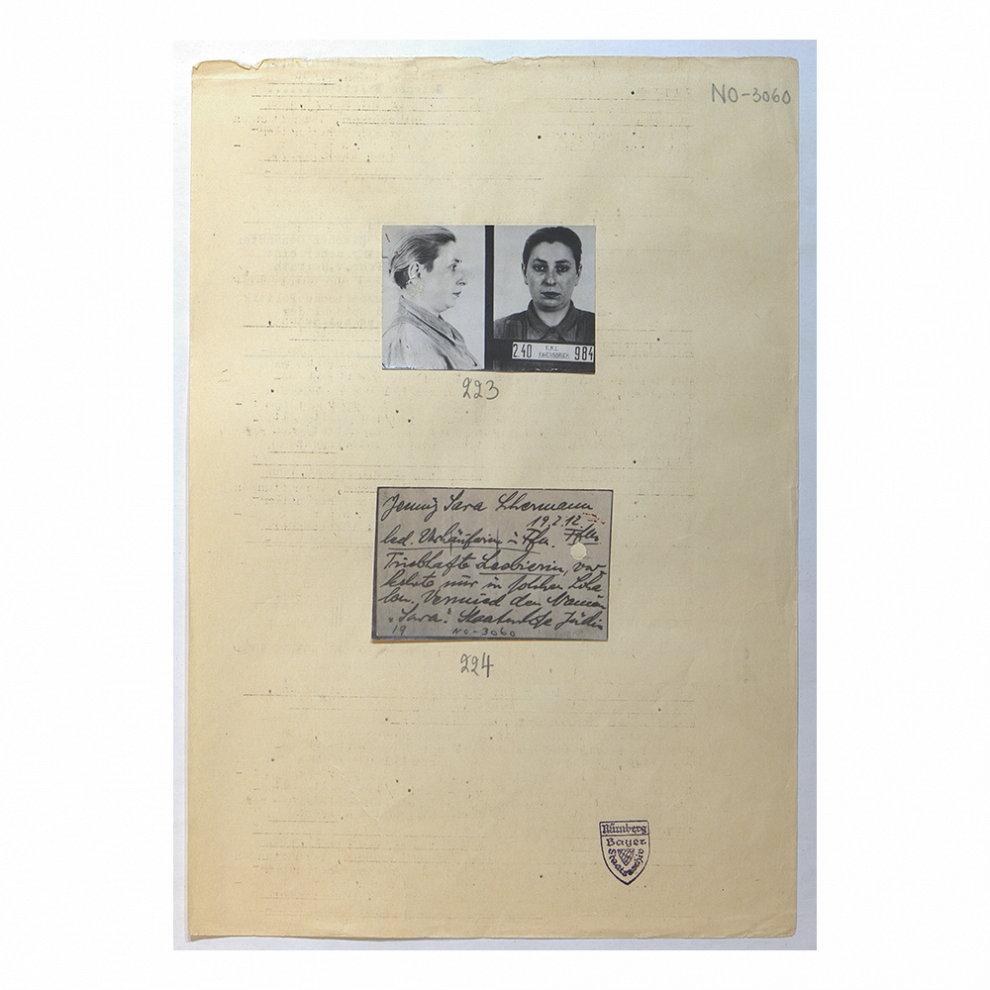

Lesbians

The Nazi regime considered lesbianism a secondary and easily controllable phenomenon. It was not criminalized when Paragraph 175 was amended. Their subculture was destroyed, but most lesbians escaped repression—as long as they remained discreet and conformed to gender norms. In this hostile climate, some chose exile or contracted fake marriages. Women were arrested under other pretexts, although homosexuality could be an aggravating circumstance. In Austria, which criminalized lesbianism, the number of convictions rose sharply after the Anschluss.

When these women were deported, they did not wear a pink triangle but were registered as Jews, political prisoners, asocial individuals and/or criminals, depending on the case. There are few traces of their presence in the camps, where they were often humiliated and raped. Some had to prostitute themselves in the camp’s brothel in exchange for the promise of being released afterwards.

Women sometimes formed homosexual relationships in camps such as Ravensbrück, but were severely punished if found out. Lesbian inmates could also suffer from being shunned by their co-detainees, especially since female kapos, and some who wore black or green triangles (criminals and “asocials”), were considered masculine (they were nicknamed “julots” (butch) and accused of being homosexuals (Germaine Tillion, Le Verfügbar aux enfers, 1944-1945).

Portrait

Eva Kotchever (1891-1943)

Chawa Złoczower was born in 1891 in Mława (Poland, then under Russian rule). At 21, she emigrated to the United States, changed her name to Eve Adams and met Emma Goldman as well as other anarchist activists and intellectuals.

Nazi Europe

The plight of homosexuals in countries allied with, annexed to or occupied by Germany could vary widely.

Paragraph 175 applied only to citizens of the Reich, Germans and inhabitants of annexed territories. Viewing homosexuality as a form of social decay, the Nazis did not care about its presence, or even considered it beneficial, in peoples deemed “inferior”.

The situation in the former Austro-Hungarian Empire was highly complex. Paragraph 175 was enforced in the annexed Sudetenland, but in the Protectorate of BohemiaMoravia, created in 1939, German, Austrian, Hungarian or Polish law could apply depending on the area and ethnicity. Austrian and Hungarian laws were more lenient, while Poland did not criminalize homosexuality at all.

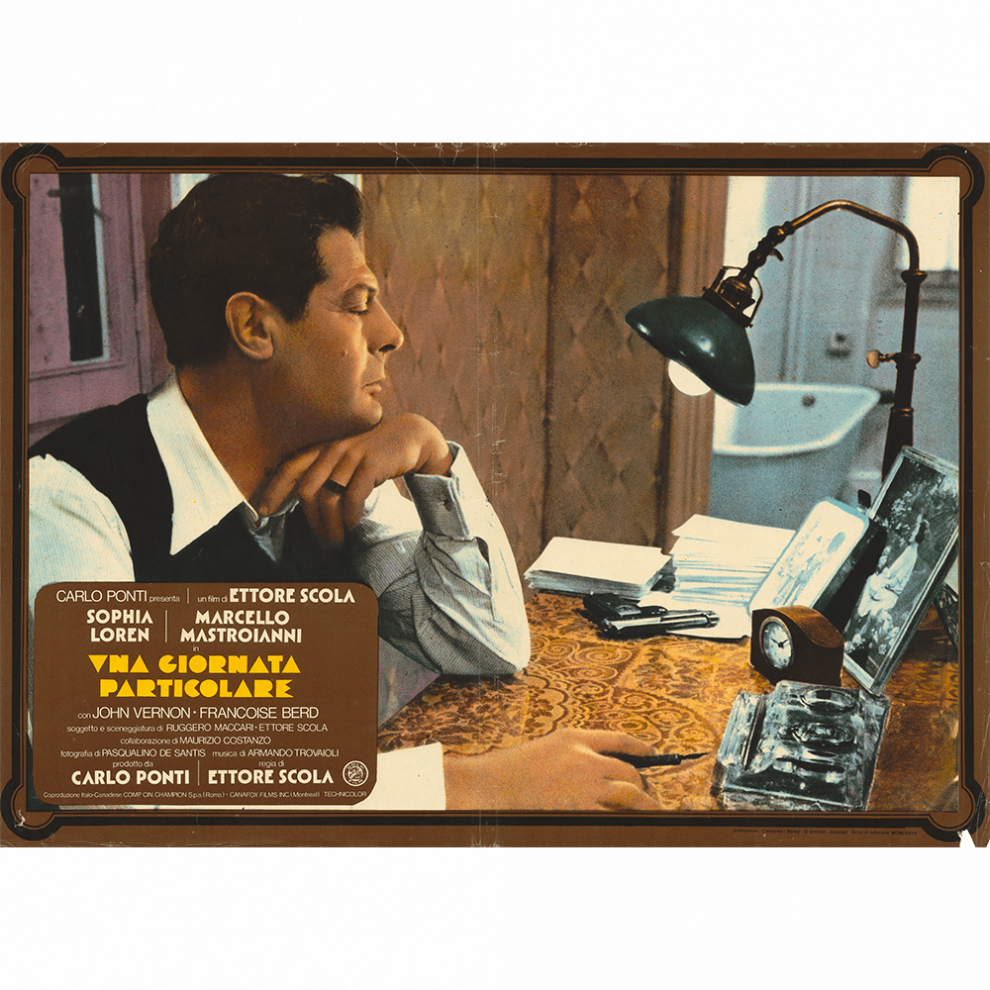

In the Netherlands, Paragraph 175 was introduced in 1940 alongside Section 248(a) of the Dutch Penal Code, which already criminalized homosexual relations with minors, but it was not systematically enforced. Homosexuality was legal in Italy, where some 100 “passive pederasts” were exiled to the Tremiti Islands from 1938 onward. Some had their sentences commuted in 1940; others were evacuated in July 1942.

Among the Allies, sex between men was a criminal offense in Great Britain, the United States, the USSR (since 1934) and others. Three neutral countries decriminalized homosexual relations between consenting adults: Iceland in 1940, Switzerland in 1942 (except in the army) and Sweden in 1944.

In France, the situation was complex.

On August 6, 1942, the Vichy regime enacted a law setting the age of sexual majority at 21 for relations between persons of the same sex, compared to 13 for heterosexual relations, but its impact was limited. Underground homosexual life went on in France, especially Paris, in bars, clubs and the circles revolving around such figures as Jean Cocteau and Suzy Solidor.

Collaborators lashed out at “inverts”, considering them, along with others, responsible for the defeat. After the war, the Resistance depicted homosexuals as collaborators (Abel Bonnard, nicknamed “la Gestapette”, Robert Brasillach, Maurice Sachs, Violette Morris, etc.), completely ignoring the fact that its ranks included many homosexuals and lesbians (Roger Stéphane, Pascal Copeau, Daniel Cordier, Claude Cahun, etc.).

In Occupied France, only German military courts could prosecute under Paragraph 175. In German-annexed Alsace-Moselle, the French Penal Code remained in force until 1942, with Paragraph 175 gradually being phased in from 1941. Trials were rare until 1942, but prosecution could be retroactive and sentences harsh. Extra-judiciary repression of homosexuality began intensifying in Alsace during the summer of 1940: homosexuals were put on file, expelled to “interior” France and detained at the Schirmeck security camp. Some were released, some expelled and others sent FRANCE to concentration camps after a prison term.

Portrait

Rudolf Brazda (1913-2011)

Born in Saxony to Czech parents, Rudolf Brazda was not 20 years old when the Nazis came to power. Beginning in 1935, he and his friends were involved in several investigations for violations of §175.

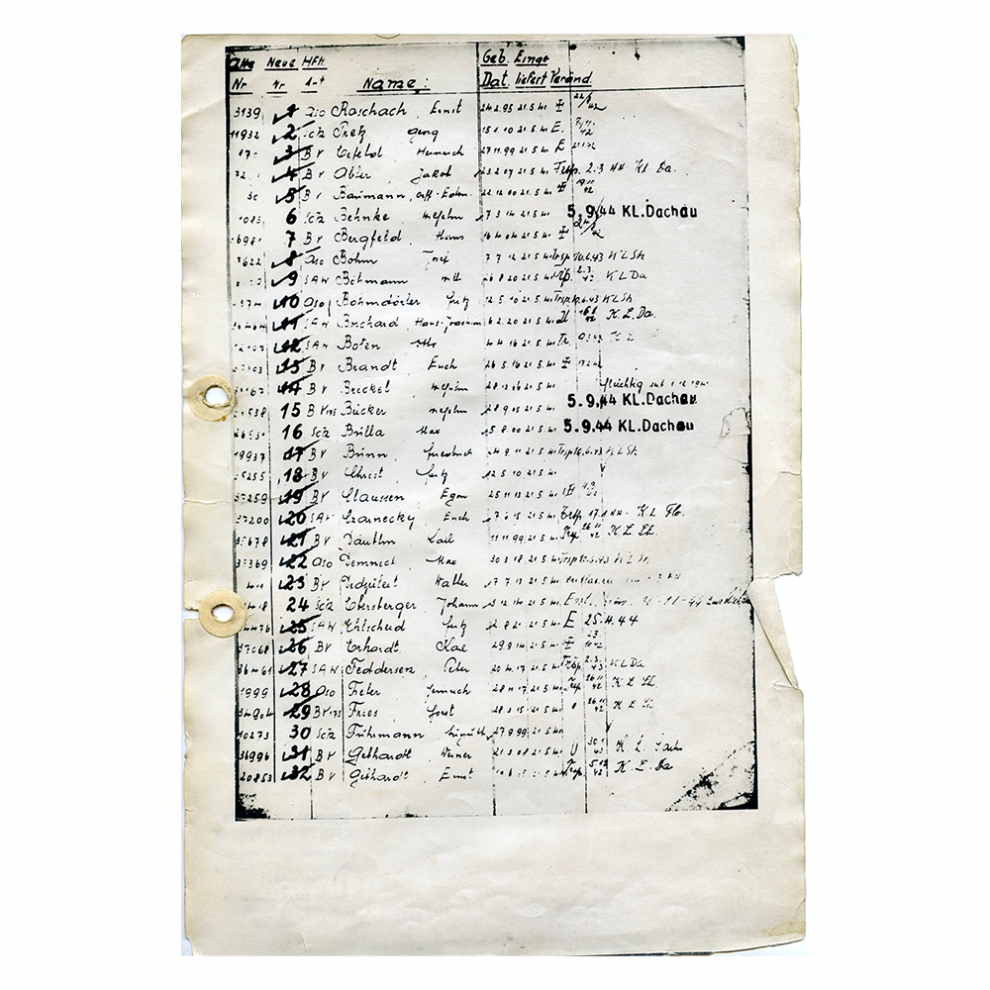

Repression of Homosexuality (1940 – 1945)

In annexed Alsace and Moselle

At least 39 people in Moselle and 371 in Alsace were affected, mostly French. of these, at least 140 were sentenced by the courts, 115 interned in the Schirmeck security camp and 92 expelled to Unoccupied France. Ten died in detention or as a result of the repression. In addition, 315 men deported for homosexuality, mostly Germans, 13 of whom were French (eight died), were interned in the Natzweiler concentration camp.

In the rest of France

At least 94 cases: 50 were administratively interned by the French authorities, of whom three died in detention and eight were deported following evacuation measures decided by the Germans; 35 were convicted by German military courts under Paragraph 175, of whom 23 served their sentence in France and 12 were deported to German prisons; nine were deported by the Sipo-SD in transports that left Compiègne for concentration camps. In all, at least five died in deportation and one just after his return.

Frenchmen in the territory of the Reich

Procedures under Paragraph 175 targeted at least 115 French civilian workers and prisoners of war in Germany. All received prison terms; at least 80 were released after serving out their time. Three died in detention, another before his repatriation and another after returning to France.

These figures are based on the current state of research conducted by Arnaud Boulligny, Jean-Luc Schwab and Frédéric Stroh.

Portrait

Joseph Regisser (1892-1952)

A merchant in Strasbourg, Joseph Regisser has led a «homosexual life» since he was 28 years old. The German annexation of Alsace forced him to be cautious.

The long wait for official acknowledgement

Ignored testimonies, continued repression

In the aftermath of the war, few homosexuals testify to the fate of themselves under the Nazi regime, even if some witnesses, such as Eugen Kogon (L’État SS, 1946), evoke the presence of pink triangles in the camps, and if homophilous magazines, such as Arcadie (1954-1982) in France, mention it occasionally.

In Germany, homosexuals are not only denied the status of “victims of Nazism”, but are still likely to be condemned under §175, which was in effect until 1969 in the FRG and until 1968 in the GDR.

In France, the law of 1942 was not repealed until 1982. The psychiatrization of homosexuality increased, in the West as in the East.

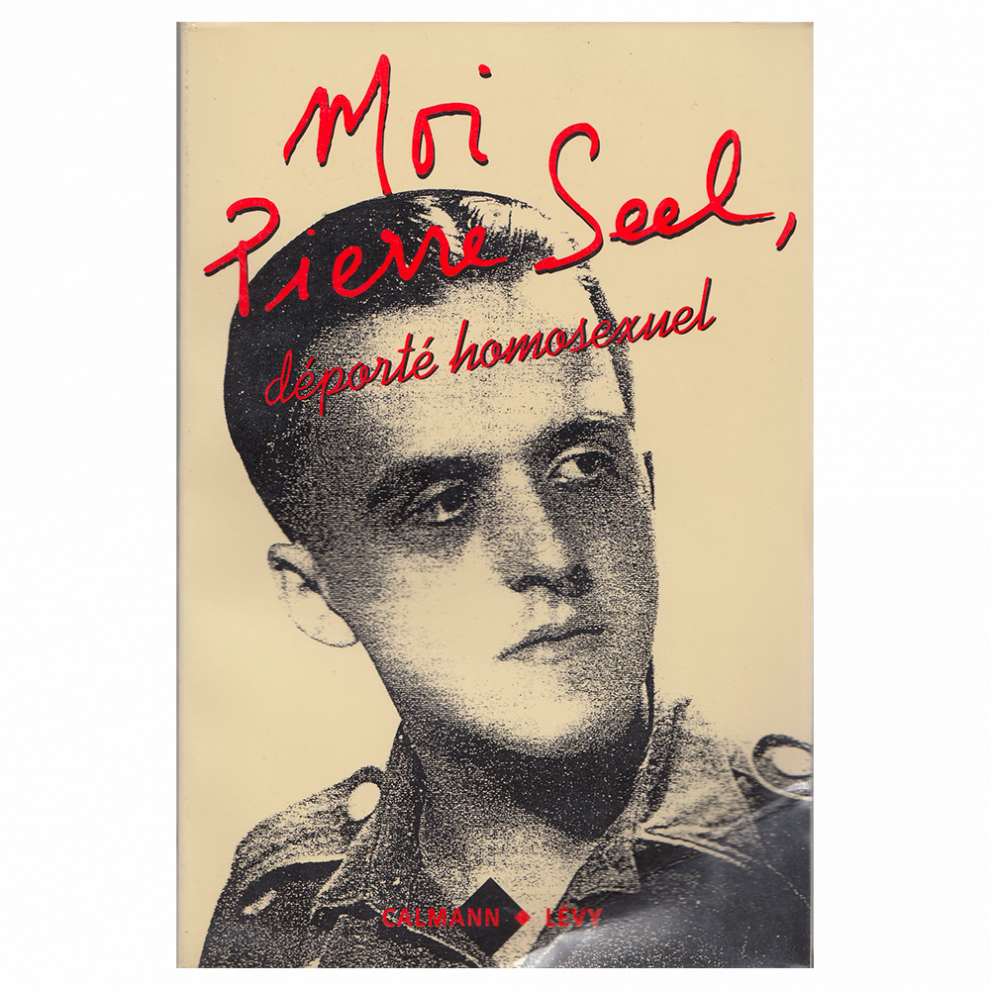

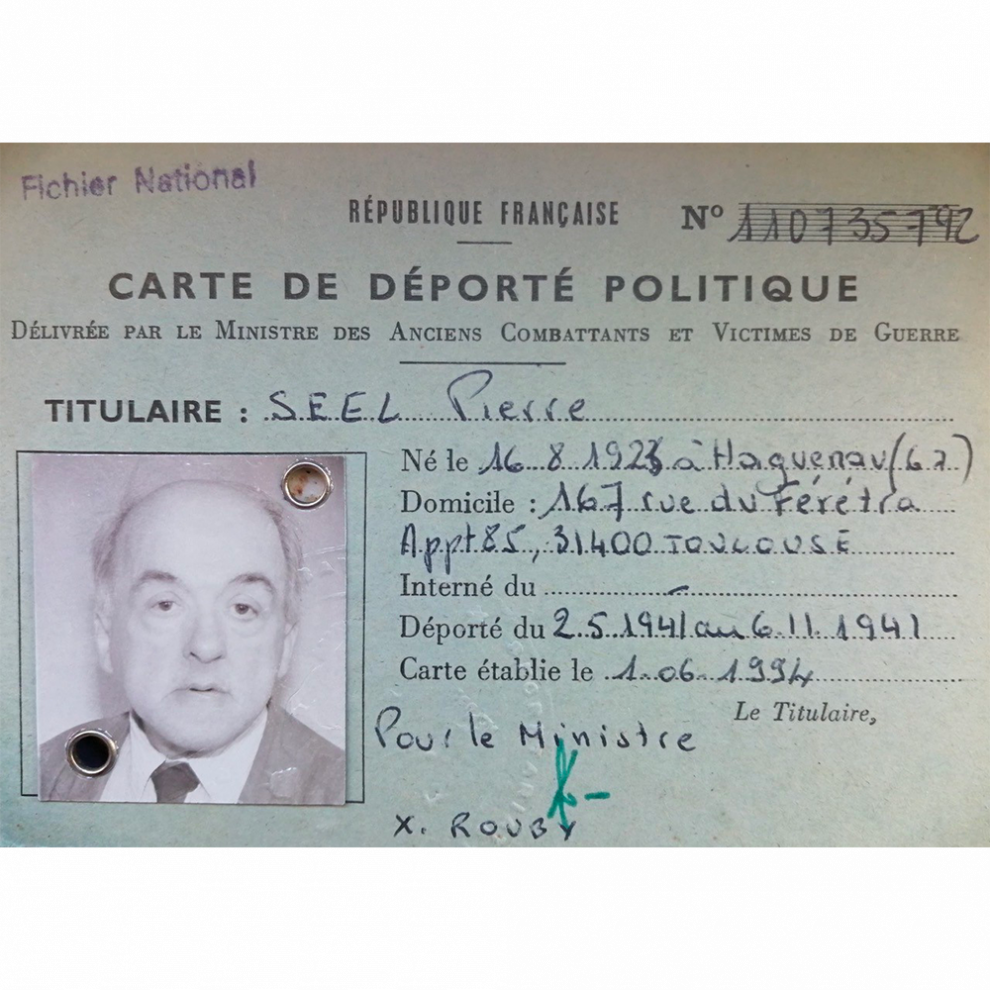

It was not until the 1970s that deportation on the grounds of homosexuality was openly debated under the influence of gay and lesbian liberation movements. Uncertain figures are often exaggerated. The testimony of Heinz Heger (1972), an Austrian pink triangle, dates, as later, in France, that of Pierre Seel (1994).

With Bent (1979), a play by Martin Sherman brought to the cinema in 1997, homosexual deportation began to be known to the general public. The pink triangle, sometimes inverted, stands out as a referent LGBT identity, used for example by Act Up in the fight against AIDS.

The long time of official recognition

In 1975, in Dachau, in the FRG, and in 1983, in Buchenwald, in the GDR, homosexual associations attempted to lay wreaths in memory of pink triangles. In May 1985, West German President Richard von Weizsäcker publicly acknowledged the persecution of homosexuals under the Nazi regime. On 17 May 2002, the Bundestag finally voted to rehabilitate – for many posthumously – men sentenced under §175 during the Nazi period, paving the way for their compensation.

In France, during the Remembrance of the Deportation ceremonies, homosexual associations clash with veterans’ associations, in a sometimes tense climate. It is necessary to wait for the speech of Lionel Jospin of April 26, 2001, confirmed by that of Jacques Chirac, of April 24, 2005, to begin the beginning of an official recognition.

Today, monuments (Homomonument, Amsterdam, 1987; Tiergarten, Berlin, 2008…) and plaques (Neuengamme, Hamburg, 1985; Natzweiler-Struthof, 2010…) honour the memory of the homosexual victims of Nazism. Documentaries (Paragraph 175, by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, 2000) tell the story of the survivors. Scientific research has taken up the subject, proposing analyses of the German case, and more and more of the allied and occupied countries. In France, work has multiplied since the 2000s, making it possible to specify the nature and extent of repression on its territory.

Memorials

Monuments and plaques honoring LGBT victims of Nazi repression include a plaque at the site of the Neuengamme concentration camp, near Hamburg (1985); the Homomonument in Amsterdam (1987); the Berlin Tiergarten Memorial (2008); and a plaque at the Natzweiler-Struthof camp (2010). The Gedenkkugel at Ravensbrück (2015), an associative memorial project specifically dedicated to lesbians, is pending approval.

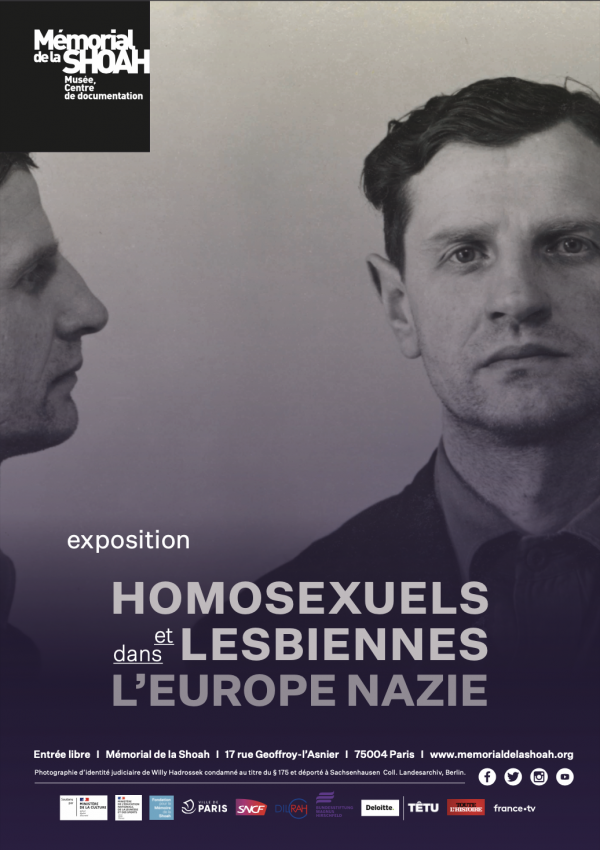

The persecution of homosexuals and lesbians in Nazi Europe: the long time of recognition

Interviews.

Directed by Natacha Nisic.

Production of the Shoah Memorial, Paris.

Suzanne Robichon

essayist and feminist and lesbian activist

Jean-Luc Schwab

historian, president of the National Amicale Natzweiler-Struthof

Frédéric Stroh

doctor of contemporary history